The town of Palazzolo Acreide is situated 43 kilometres (27 mi) from the city of Syracuse in the Hyblean Mountains. Its cemetery is a city of stone for itself and probably hosts more inhabitants than the town has living ones.

“Il Giorno dei Morti” had been the day before yesterday, and we found the cemetery dotted with flowers. The air was saturated from the scent of lilies, with the herbal aroma of the chrysanthemums wavering in between. The after noon sun shone on granite and sandstone, there were impressive family vaults in the shape of small cathedrals, and graves so massively lidded with marble slabs that even on the day of resurrection the dead underneath would not be able to lift them …

The dead here do not rest in earth, or do they? By what means are these massive stones lifted then?

Many gravestones were adorned with finely chiseled rose garlands, quite in the style of softly rounded rococo roses (in contrast to rose reliefs on German cemeteries that usually show a tea-hybrid style rose). Maybe this was a specialty of the local stonemason at that time.

All gravestones carried oval enamel or porcelain plates with a portrait of the deceased, the majority of them in black and white. Stern faces, many of them young. Some men were portrayed with their sunglasses on. Among the women there were many beauties that had died in their early 20s or 30s. No one was smiling (except for a lady on a 1980s colour photograph). Time and sunlight and rain had worked on the surface chemistry of the portraits: Silvery lines and spots obscured parts of the face, or partly changed their expression. It made them reminiscent of photographs of ghost séances –with the ectoplasma appearing as a silvery or white substance in the picture. But even without blemishes many faces spoke clearly of the hardships of Sicilian life: black eyes staring relentlessly back at the visitors, hairdos worn like invincible castles, and an unspoken sadness in the lines of the mouth of all of them.

There were rose bushes too, growing by the side of the gravestones. By the size of their branches they must have been old. 50 years, 70 years and plus. I kept wondering why or who would plant a rose in between either two graves or just at the border of a stone. “These roses”, said Patti, “maybe just fell out off the bouquets or wreaths and took root.” “These are grafted roses”, I said, “I don’t believe so”.

We passed dozens of bushes, each almost directly growing from under a grave. In my imagination all those roses had been there first. Maybe this place had been a former rose garden. Or, when the cemetery was founded, the graves were smaller and earth only with a small stone. Any rose bush planted at that time could continue to grow after having graciously endured the great marble immortality of the late 1940’s.

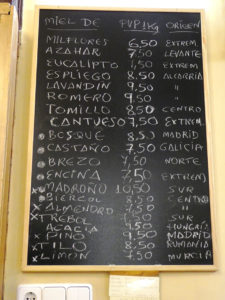

La Casa de la miel has been in the hands of his family ever since the shop was founded in 1946, its owner, Pedro Pajuelo, says. We are standing in front of the counter, a black board next to the door shows the different kinds of honeys sold here, a shiny bin with a giant bee printed on it decorate the counter as well as an old-fashioned scale made from white enamel.

La Casa de la miel has been in the hands of his family ever since the shop was founded in 1946, its owner, Pedro Pajuelo, says. We are standing in front of the counter, a black board next to the door shows the different kinds of honeys sold here, a shiny bin with a giant bee printed on it decorate the counter as well as an old-fashioned scale made from white enamel.

(Translation follows, sorry) Der Florettseidenbaum, gehörig zur Familie der Malvengewächse, Unterfamilie Wollbaumgewächse, verblüfft durch einen ausgesprochen wehrhaften Stamm… und Unmengen handgroßer pinker Blüten. Dieser hier begegnete mir im Royal Botanic Garden in Melbourne.

(Translation follows, sorry) Der Florettseidenbaum, gehörig zur Familie der Malvengewächse, Unterfamilie Wollbaumgewächse, verblüfft durch einen ausgesprochen wehrhaften Stamm… und Unmengen handgroßer pinker Blüten. Dieser hier begegnete mir im Royal Botanic Garden in Melbourne.