16th Century Thistles: Visiting the Library of the RJM

A place for study, information but also a treasure trove of ancient books on botany, this is the library of the Real Jardìn Botanico. Felix Alonso is the head of the library department – we already met when I stumbled into the offices on my very first visit to the garden – and we both enjoy our second encounter. As requested I had prepared some questions and the interview runs smoothly (in the process of editing).

A place for study, information but also a treasure trove of ancient books on botany, this is the library of the Real Jardìn Botanico. Felix Alonso is the head of the library department – we already met when I stumbled into the offices on my very first visit to the garden – and we both enjoy our second encounter. As requested I had prepared some questions and the interview runs smoothly (in the process of editing).

Felix Alonso, head libarian of the RJM explains about his work

Sample Title :)

The beginnings of the book collections stored here lie in the 18th century, but since then the work of librarians has changed considerately – more so with the impact of the digital age. Apart from keeping pace with the mounting bulk of new publications (and sorting and cataloguing them), the library also engages in several activities with the public. One of them being the forthcoming exhibition about „Tulipan Ilustrado“, the Tulip in Illustration, on the 20th of March (until 20th of May).

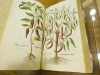

Speaking of illustrations Felix proceeds to show me one of the more special books. The drawings are excellent (naturally!) and separated by tissue paper from each other. Pages are turned and the rustle of the tissue compels me to record the sound. Señor Alonso smiles. Maybe this seems strange to him, that something so utterly functional has qualities beyond that: audible ones. Then again, this might have been to moment for him to decide to let me walk me further into the aisles.

Of course this is the goddess Flora

Fantastic books if you love the green world!

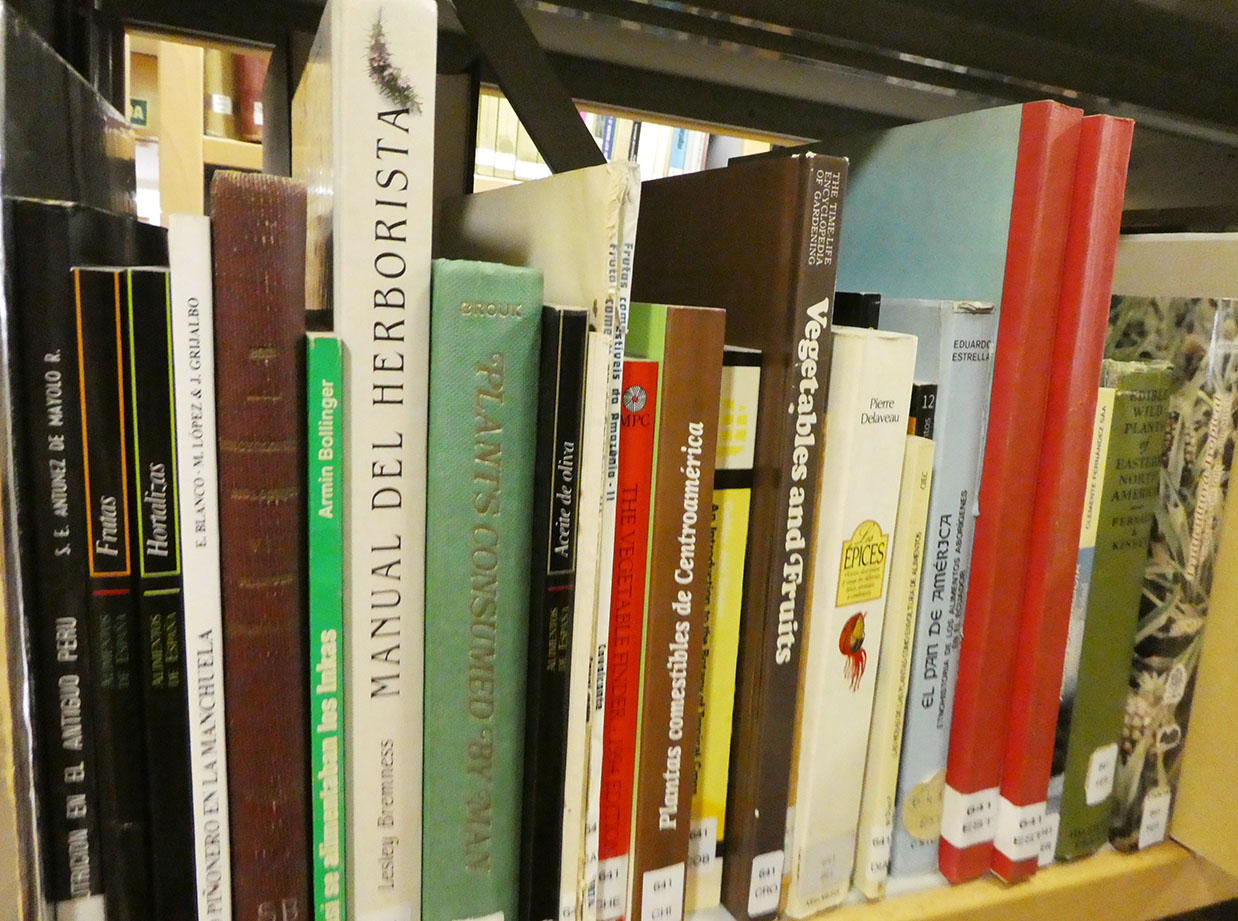

Needless to say that I am overwhelmed by the abundance of botanical books in the shelves, some of them surely rare: Expedtion reports from the jungles of Bolivia, mushrooms in the Himalya, pittosporums in Galicia, Pilze in Mitteleuropa, books in Chinese, German, English, French, and and and. Yet, if my curiosity hadn’t driven me down the corridor on that first day I wouldn’t have known about the cabinet at the very end of the room, and so I ask.

„Yes, says Felix, I can show you at least one of the books, I only need to get the key.

The Fuchs Book

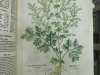

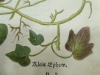

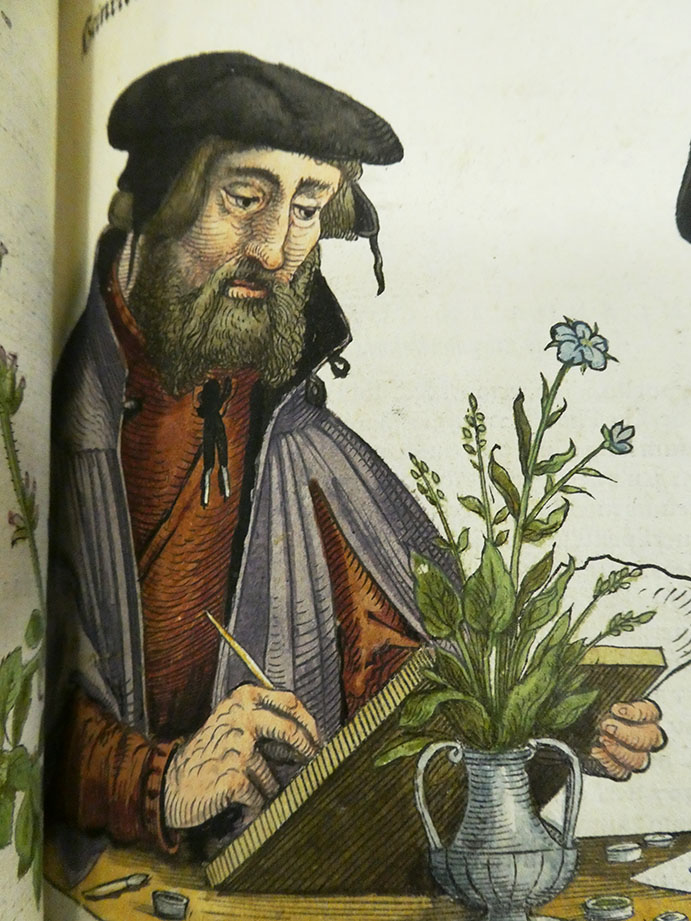

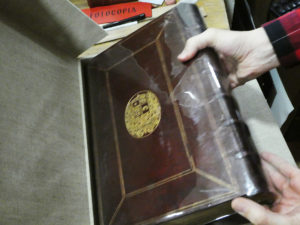

These treasures are stored in grey plastic boxes, and carefully wrapped in transparent foil. The book I am allowed to look at is one of the very few (maybe 50 worldwide) copies of Leonhard Fuchs, one of the „fathers“ of botanics, printed around 1542.

The index indicates the plant names in latin but also with their common German names. The drawings were first printed in their outlines and afterwards coloured by hand. I am stunned and feel an overwhelming gratitude for the existence of these botanists, maybe of botanists in general. And, of course, for the people that helped to manufacture books like this, woodcutters, painters, printers. Fuchs himself acknowledges their input by the inclusion of their portraits. Else? Look for yourself! And thank you, Señor Alonso!

After the talks a quick picture

As I leave the offices of the library, the Botanic garden sparkles in sunlight. Despite the still-too-low temperatures the plant make every effort to spring into leaf and flower… while the gardeners are working hard to prepare more beds.

Almond tree bonsai at the entrance of the library

This post is also available in: German